Flying Scotsman is 100 years old! Here is the story of the famous locomotive. In this not-so-romantic blog, we look at Flying Scotsman at 100.

Personal opinion first

Flying Scotsman is arguably the most famous steam locomotive on the planet. From being broken when it was chosen to attend Wembley Arena, to almost being scrapped in the 60s to having legions of fans following it around the country.

This blog will tell the story of the Flying Scotsman, but I wanted to get my own personal opinions out of the way to begin with as they may come through naturally.

In my own personal opinion, I strongly dislike the hype around Flying Scotsman and the locomotive in general. It obviously gets a lot of people talking and interested in the railways which is fantastic. But, as a whole, there are better and more notable locomotives which are overshadowed by what is- if I’m being generous- an above-average locomotive at best.

My opinions have seen me get shouted at and called all sorts of names (sadly not a joke) and probably means that 90% of people have clicked out of the blog. My challenge to the people who are angered or disagree with my opinion- in the comments leave me a list of 4 or more reasons why Flying Scotsman is or should be famous. I’d really like to see them.

For me, Flying Scotsman is so popular because it has benefited from an extremely good marketing team and everyone feels like they have to like it. It definitely feels like if you like railways you feel pressured into liking Flying Scotsman- mostly because people get extremely angry if you don’t.

Now I’ve annoyed all the Flying Scotsman fans and, putting my personal opinions to one side, let’s get into the story of Flying Scotsman.

Just to quickly clarify, this blog is looking and talking about Flying Scotsman the locomotive, not the express passenger train service that went between London and Edinburgh. Lots of people get confused between the two, so let’s make sure we’re not those people.

1923- Doncaster

Flying Scotsman was built at Doncaster works at the cost of roughly £8000. It was completed in February 1923 after being designed by Sir Nigel Greasley who would go on to design the world’s fastest steam locomotive, Mallard.

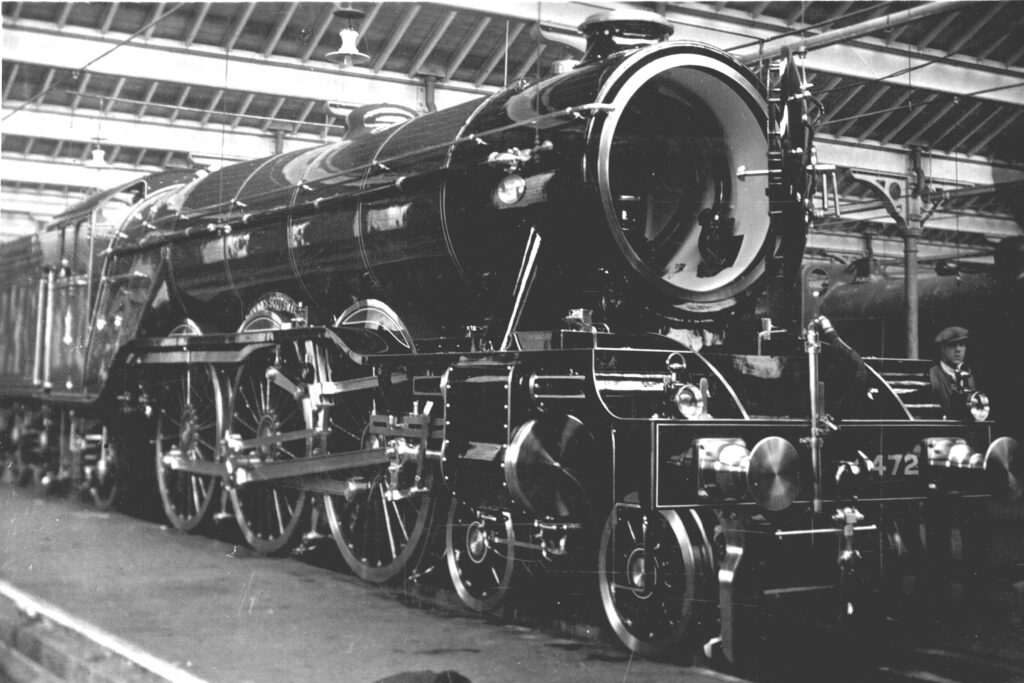

When it rolled out of Doncaster works it had the number 1472 on its side as it was built when the Great Northern Railway had just been absorbed into the London North Eastern Railway (LNER) and a new numbering system hadn’t been put in place yet. It wasn’t until 1924 that Flying Scotsman got its more famous number, 4472.

From 1923 to 1947, Flying Scotsman was an A1 class. From 1947 onwards it was an A3 class. You’ll be grateful to hear/read that I’m not going to go into all the details of the differences between A1 and A3, mostly because I can’t be bothered… and because it’ll come up in a not-so-romantic railways book in the near future.

Flying Scotsman was named after the London to Edinburgh service when it represented the company at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park. The exhibition featured displays from all across the former British Empire. It was broken at the time when LNER needed to send a display, hence why it was chosen to go.

The Flying Scotsman route was made non-stop in 1928, allowing passengers to travel from London to Edinburgh (or Edinburgh to London) in around 8 hours without stopping. Flying Scotsman (the locomotive) pulled the first non-stop service on the 1st of May 1928.

Fast forward to the 30th of November 1934, Flying Scotsman became the first steam locomotive to officially travel at 100 miles per hour. The word officially is an important one.

In 1904, a Great Western Railway locomotive called “City of Truro” was said to have reached 100 miles per hour, and it’s more than likely that it did. The problem is the City of Truro’s record wasn’t official. So, in the history books at least, Flying Scotsman was the first steam locomotive to travel at 100 miles per hour.

As the A4s like Mallard came in, Flying Scotsman became less and less of a flagship for LNER and after the Second World War, started to go through locomotive numbers like they were going out of fashion.

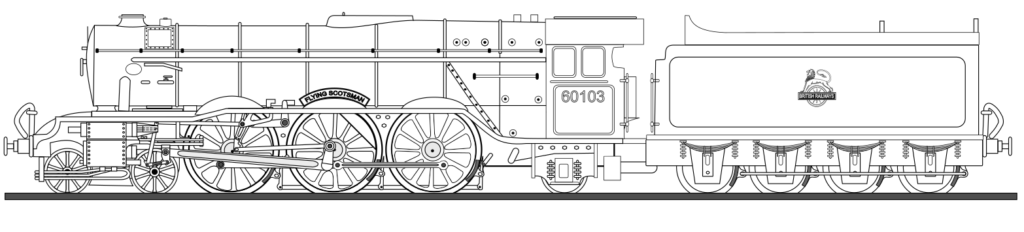

It was numbered 502 for 5 months at the start of 1946 before a change of heart and becoming 103 from May 1946 until the arrival of British Railways when it became 60103 because British Rail added 60,000 to existing numbers. Why not I suppose?

Flying Scotsman ran for British Rail until it was retired in 1963, it had been announced the locomotive would be scrapped on retirement so, after its last service from London Kings Cross to Doncaster, Flying Scotsman headed for the scrap pile.

SAVED FROM THE SCRAP PILE

That could, and maybe should, have been the end of the Flying Scotsman story, but Alan Pegler had other ideas. He had first seen the Scotsman back in 1924 at the British Empire Exhibition and had an emotional connection to it. He bought the locomotive for £3500 in 1963. A lot of money right? But this was only the start of how much money Scotsman was going to need for its preserved life.

The first stop for Scotsman was the Doncaster workshop where it was given a needed, and fairly expensive, dose of TLC (tender love and care). Pegler had Scotsman put back into its LNER days. This meant a change of paint, getting rid of smoke deflectors, returning it to only having a single chimney (all engineering terms- don’t worry too much about them) and it even got a corridor Tender back! A corridor tender is the bit that is pulled behind the locomotive where the coal and water are stored, a corridor Tender is one with a corridor in so you can swap crews.

Flying Scotsman’s first excursion (fancy word for journey) was on the 10th of April 1963 when it travelled from London Paddington Station to Raubon in Wales (and back again). An estimated 8000 people were at Paddington Station to see it depart.

It only took around 2 years for Scostman to recoup the £3500 it cost to buy, which in an investment world is a good return. Unfortunately, a lot of the refilling stations for steam locomotives were being removed on the mainline so Pegler had to splash out on a second Tender which was converted to be a second water tank, so rather than having coal and water in, the second Tender just had water inside, meaning Scotsman could do longer journeys without fear of blowing up. At the same time, he also bought some spare parts from a scrapped locomotive called Salmon Trout, which was or had been the same type of engine as Flying Scotsman.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the first non-stop run from London to Edinburgh, Flying Scotsman did the journey again in May 1968 which was the year that steam travel was gotten rid of on British Railways. A locomotive called Oliver Cromwell was the last official steam train on British Railways on the 11th of August 1968.

AMERICA CALLING

Flying Scotsman headed to the United States and Canada in 1969, a cowcatcher (looks like a small snow plough on the front of the locomotive) and a bell (a literal bell), a headlamp and air brakes were added to the locomotive.

The first journey was from Boston, Massachusetts to Atlanta, Georgia via New York City and Washington D.C before heading south to Texas. The tour in the United States didn’t go very well though. They had strict laws about running steam on their railways as they were a massive fire risk so instead of running under its own steam, Scotsman had to be pulled by diesel locomotives. And if Pegler had had any plans of making some much-needed cash from being in the United States they were thrown out as none of the trips on the tour carried any paying passengers as it would have been illegal to do so.

In 1970, Scotsman travelled from Texas to Wisconsin and then to Montreal. In 1971 it travelled from Toronto to San Francisco. A total of 15,400 miles. Flying Scotsman was a commercial success in the States but it left Pegler £132,000 in debt at the end of 1971, Flying Scotsman was now trapped in America. Pegler made sure it was stored in a US Army depot in California to stop creditors being able to rip bits off it and he returned back to England, having to work on the cruise ship to pay for passage, and started giving lectures about trains and was even named the chairman of the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales.

William McAlpine and Australia

William McAlpine became Scotsman’s saviour and paid off the creditors and was now the new owner of the steam locomotive. His first job was to bring Flying Scotsman back to Britain and did so via the Panama canal- it was on a boat. It then travel across the Atlantic Ocean (again on a boat) to Liverpool where it travelled under its own power to Derby where it was overhauled.

A locomotive overhaul is basically when a locomotive is taken apart and put back together with some new bits where the older bits have broken. Consider it a huge service, like a really intense MOT for a car.

Scotsman ran some more excursions but it wasn’t very long until it was forced back into the workshop for major repairs- this would be a common theme moving forward.

If you’d looked in Britain for the Flying Scotsman in October 1988 you would never have found it- because it had gone to Australia. Flying Scotsman was actually the second choice to go to Australia and attend Aus Steam ‘88 as the event organisers had wanted Mallard to go- but Mallard was unavailable because it was its 50th anniversary of breaking the steam speed record.

Flying Scotsman got some more miles in its wheels whilst in Australia with a total mileage count of 28,000 miles. During its adventure down under, Scotsman travelled 422 miles without stopping- becoming the record holder of the longest non-stop journey by a steam locomotive.

Flying Scotsman was back on British rails at the end of 1989 and in 1993 Pete Waterman joined the Flying Scotsman team running the business side of a newly formed partnership.

In 1995 Scotsman derailed and a large crack between the boiler and cab formed…. Back to the workshop then.

Tony Marchington

Tony Marchington bought the locomotive and all its carriages for £1.5 million after McAlpine and Waterman ran into financial difficulties. He then spent another £1 million to get it back up and working. It took them 3 years to get it back ship shape- well, locomotive shape.

After its overhaul Scotsman went back to running excursions and even had a documentary made- it is quite a good documentary. But Scotsman was still a money sink.

In 2002 Marchington had the plan to create a Flying Scotsman Village in Edinburgh to boost revenue but it was turned down.

And perhaps a similar ending to an owner’s story- Marchington was declared bankrupt in 2003.

2004 onwards

Flying Scotsman was put up for auction and there was fear it would be bought from an overseas buyer and removed from British soil for good.

A joint bid from the National Railway Museum, Richard Branson and public donations saw NRM submit a winning £2.3 million bid to buy Flying Scotsman. After a couple of years of runs Flying Scotsman entered the workshop once more… this time for 10 years.

The future

Flying Scotsman returned to the rails in 2016 and powered itself for the first time since 2005 and has done plenty of runs since.

Now it’s 100 years old, there are celebrations and special runs planned.

Will it still be running in 100 years? I highly doubt it.

Recommended blogs

If you’ve enjoyed this blog about the Flying Scotsman then here are some other blogs I suggest you read next.