As the American railroads were starting to grow a small locomotive built in Newcastle by the name of John Bull travelled overseas to operate. This is that story—the story of John Bull- the locomotive.

Table of Contents

The Camden and Amboy Railroad

The Camden and Amboy Railroad was the first railroad to be built in New Jersey and was one of the earliest Railroads to be built in North America. It was granted permission to be built on the 4th of February 1830 and had the ambition and goal (are they the same thing?) to connect the Delaware River to the Raritan River. This would allow them access from Philadelphia (where I was born and raised… sorry couldn’t resist) to New York City which would mean money… lots and lots of money.

The problem for the newly formed Camden and Amboy Railroad was that on the same day they were permitted to survey land to build the railroad, a canal company called the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company was also given permission to build a new canal to connect the Deleware and Raritan Rivers together.

The idea of the canal actually started back in the 1690s when the founder of Pennsylvania William Penn suggested a canal would be a good idea.

In the end, neither the canal nor the railroad were built where they were originally planned thanks to land quality and other boring reasons, but between the two of them, they did connect New York and Philadephia. These two cities were the two largest American cities at the time.

The construction of the Camden and Amboy Railroad began on the 4th of December 1830 with rail and equipment imported from Britain under the leadership of the C&A Railroad president Robert L. Stevens.

The equipment had to be imported from Britain because it was still a very new technology in America and wasn’t widely available.

There is honestly more to the story of the Camden and Amboy Railroad but it’s mostly railroads buying each other, merging and the expansion of track… I’ll leave it for another blog. In fact, I won’t…. I’ll leave it for a book.

Robert Stephenson

In the first volume of the Not-So-Romantic Railways, I spoke – albeit briefly- about Robert Stephenson. So we’re on the same page. The reason I didn’t harp on about Robert Stephenson for eighteen pages (front and back) is because everyone is always talking about Robert Stephenson and I wanted to be different, but consider this my apology to the Robert fans who feel betrayed. I do think he’s the most recurring character in the book series if that helps though.

Anyway, Robert Stephenson owned a railway company called Robert Stephenson and Company which was based in Newcastle in the North East of England. It was in this factory that the locomotive John Bull was created. (Is anyone else imagining an evil laugh?)

Once John Bull had been built in Newcastle it was then dismantled and placed into a number of boxes and shipped over to America on a ship called the Allegheny (no, I can’t pronounce it either).

To give you an idea of how slow boats were back then it took just under two months for John Bull to get from Liverpool to America. I think it takes about a week nowadays.

John Bull is born

When John Bull arrived in crates at the feet of engineer Isaac Dripps he discovered that no drawings or instructions had been sent on how to reconstruct John Bull.

Classic error.

Isaac put John Bull together using his engineering instinct and it ran for the first time on the 12th of November 1831. An interesting thought is that John Bull might have actually been put together differently than Stephenson had intended. It had a top speed of 25 miles per hour but what if the way Stephenson had built it meant it could have actually gone 26 miles per hour?

Actually, that’s not very cool to think about, let me try again…

What if the way Stephenson had built John Bull meant it could really go 27 miles per hour?

You know what, I’m not very good at making this point sound impressive… let’s just move on…

John Bull actually hauled Napoleon’s nephew Prince Murat on its test track after he’d emigrated there in exile at some point during 1828 aged 21. A few years before that when Napoleon had been exiled from France in 1815, Murat’s father had been murdered so his mother had fled, along with Murat and his siblings to Austria. It was only when he turned 21 that he was able to head to America.

His wife was said to have hurried towards the train so she could tell everyone she was the first woman to travel on a steam-powered locomotive in the United States. It was a noble dream but sadly, for her, women had been on the first journeys of both the Baltimore and Ohio and Mohawk and Hudson railways by 1831.

When John Bull had first arrived in America it only ever ran on a test track as the railway line proper hadn’t been finished yet. Because of this John Bull faced 2 years in storage until 1833 whilst horse-drawn carts were used to finish the railway- they were literally building the track for their replacement.

With the railway complete it was time to name the locomotive, and this is where the name Stevens came into play. It was named Stevens after Robert L. Stevens who was president of the railway at the time. But, the crews who regularly used the locomotive had a better name for it.

John Bull.

What’s in a name?

The nickname came from a cartoon of the same name. John Bull in the cartoon was often used in British political campaigns and was depicted as a middle-aged, slightly chubby man wearing a union jack waistcoat and a top hat.

The name John Bull became so commonly used that I think people forgot that the locomotive was ever called Stevens. I bet Robert L. Stevens felt a little bit sad about that. Which name do you prefer, John Bull or Stevens? In fact- what would you name a locomotive- I’d one hundred per cent name a locomotive after me because I’m that big-headed.

Working life

During its early working life John Bull faced a handful of problems, the biggest being that it kept derailing (when the wheels come off the track). Derailing is not good for locomotives particularly if they’re pulling passengers who are eating soup as when they derail it causes one heck of a bump and the soup will go everywhere. They were lucky the dining car wasn’t invented for another couple of decades! At any rate, a derailment causes enough of a bump for everyone’s hats to fall off- just imagine how embarrassed everyone would be when their hat hair got revealed!

But why did John Bull keep derailing? Was the driver driving too fast because he really needed a wee and wanted to get to the destination quicker? Maybe. But the main reason was that the track quality in America was lower than it was in Britain where John Bull was built.

Yes, I did say earlier on that a lot of the track and equipment was imported from Britain. Does this mean the lower rail quality was because of lazy British engineering? Or does it mean that any track built in America was where the locos kept derailing?

You know what, I don’t even think that paragraph made sense. Anyway…

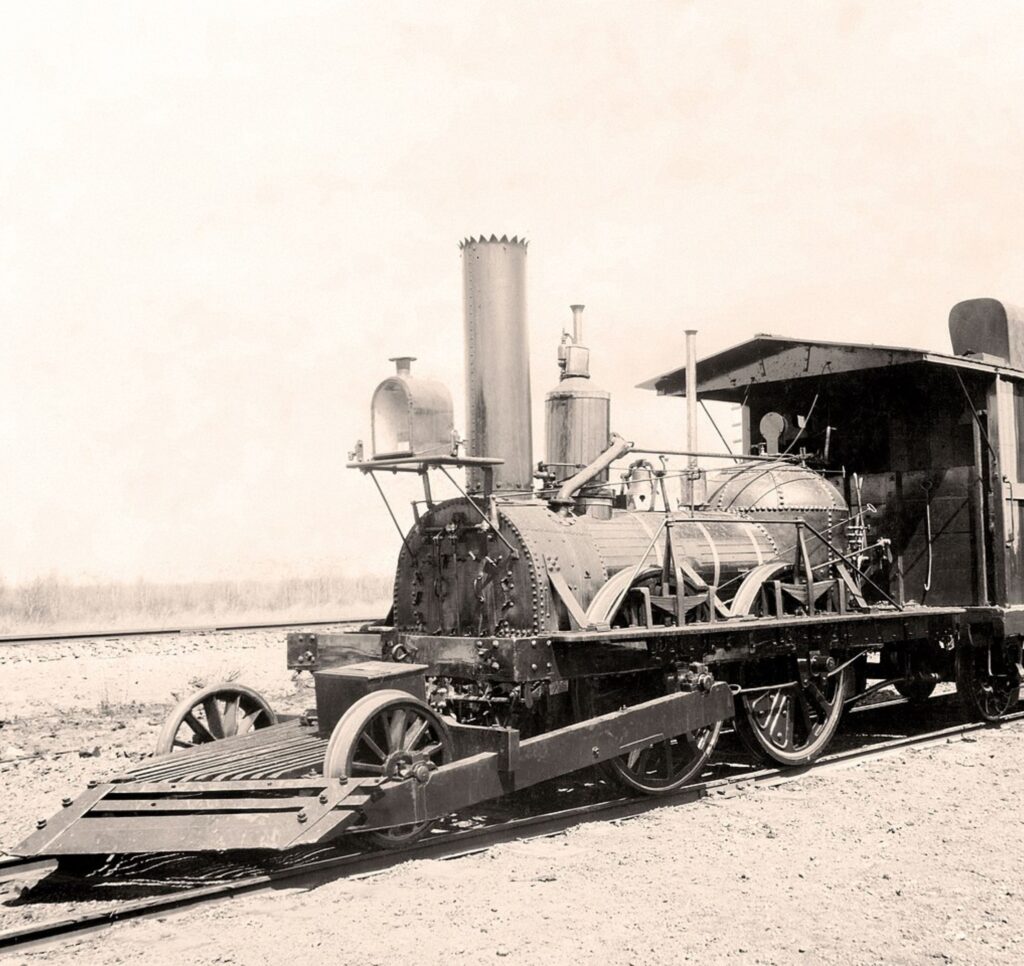

To reduce the number of derailments and the high number of complaints about passengers’ hats getting dirty the engineers got to work and added what is called a leading truck at the front of John Bull.

The leading truck was made up of two wheels on an awkward-looking frame- honestly have a look at the picture the leading truck looks like something I badly tried to make. These leading wheels helped guide John Bull around corners. The more common name for these leading wheels is bogies. (Nope- not a joke! … Please stop laughing)

To make the leading truck look even “cooler” they also added a cowcatcher which back then was called a pilot.

I wonder how many cows cowcatchers have caught over the years? I imagine it’s not even close to being possible to find out. The cowcatchers weren’t just there to catch cows though, they were also useful for knocking other debris off the track to make sure the track was clear.

I’m sure you’re wondering how cows and other animals could even get on the track as we’re used to seeing huge fences around the railways nowadays – this is a good time to remind you that you should never go on the railway, not only would it be a £1000 fine but if you were to be hit by a moving train what remained of you would fit inside a shoebox.

Back in the early days of the railways- and particularly in bigger countries- there weren’t fences on every part of the railway. It was an error on the engineers’ part really. They were so keen to build railways that they forgot about the health and safety of keeping people, animals and other things off the railway track.

The British locomotives had no need for cowcatchers as they built fences around their railways which is why you don’t see British locos with cowcatchers on the front.

Remember the engineer Isaac Dripps, who built John Bull without instructions? Well, he felt the cowcatcher should impale the animal so it could prevent the animal from falling under the wheels and derailing the engine.

It sounds like he wanted to make a giant animal kabab on the front of the locomotive! They tested this design and the first poor animal who was unlucky enough to end up on the track was skewered by such force, they needed block and tackle (rope and a pulley) to get the poor creature off.

The cowcatcher they ended up using is slightly kinder and is called “the wedge”. It was Dripps who designed that as well, and the wedge soon became the standard cow catcher design.

So Isaac Dripps could build locomotives without instructions, make animal kebabs whilst the train was still moving and design the standard cowcatcher used worldwide… what a life.

I can’t confirm if the story is definitely true but there is a story of a cow getting onto the track and instead of being pushed out of the way by the cowcatcher it ended up on top of it instead. The cow then travelled for miles for completely free! It’s an a-moo-sing thought if nothing else. Bet the eyewitnesses really milked retelling that story.

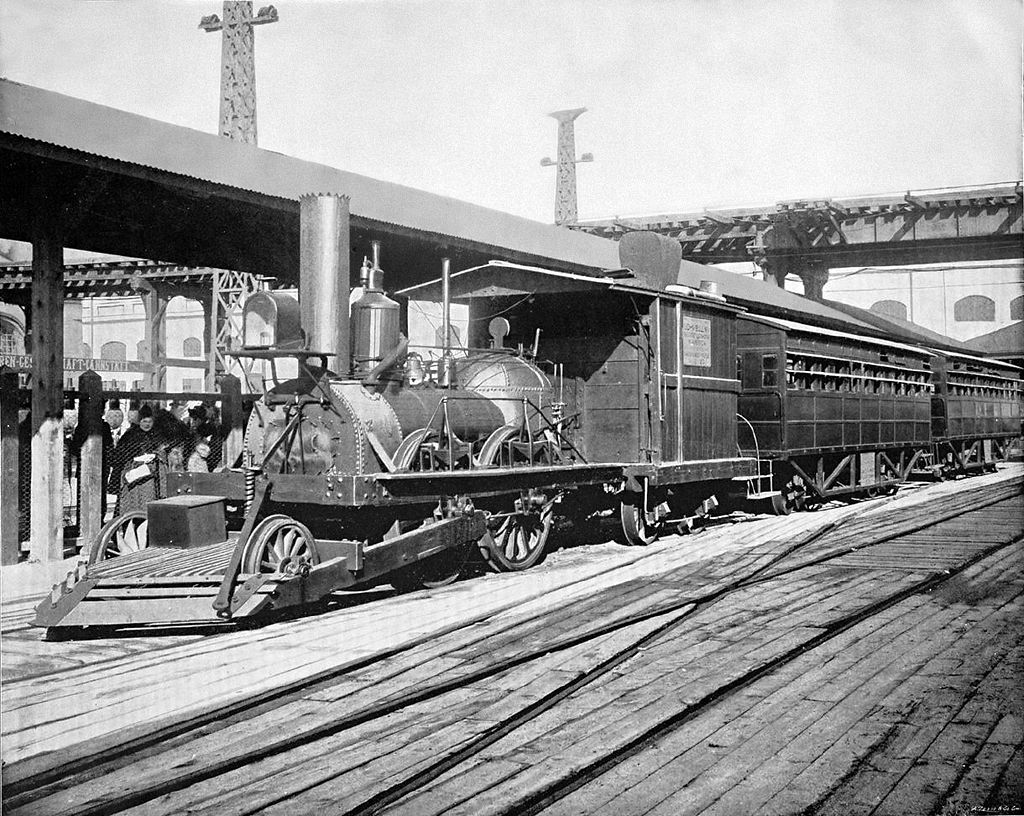

The final addition to John Bull is one that the crew would have been very grateful for… a cab to help protect them from the weather. It didn’t take them as long in America to realise that if you gave your crew some passenger comforts they would still do their job.

In 1836 John Bull was sent to Harrisburg and has the honour of being the first locomotive to operate there. Certainly not a bad claim to fame.

And for the next pleasant number of years, John Bull pulled passengers and freight between Philadelphia and New York. Because of the leaps in technology, locomotives tended not to have massively long working lives, and the same was true for John Bull.

Preserved life

In 1869 the Camden and Amboy railway was absorbed by the United New Jersey Railroad and canal company which itself was merged into the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1871. Eager for advertisement and promotion the Pennsylvania Railroad (I’ll just write PRR from now on- if I ever write or talk about it again of course) sent the John Bull locomotive to the first official world fair to be held in the United States (Centennial Exposition).

John Bull was then put on display at the National Railway Appliance Exhibition in 1883. It’s quite concerning that at the tender (that might be a train pun) age of 51 John Bull had become more of a display piece- I hope nobody starts putting me in museum exhibits when I’m 51. John Bull was bought by the Smithsonian Institution in 1885, becoming the first large engineering artefact for the Institution.

The locomotive remained on display in the East Hall of the Arts and Industries building for 80 years with only a very occasional journey into the outside world, including being on display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. The Columbian Exposition was the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in America.

The Rebirth

For the Columbian Exposition, the PRR (I did write it again!) arranged for John Bull to be partially restored so it could run the complete distance between New Jersey and Chicago which was around 800 miles… They wouldn’t have done it all in one driving session.

The PRR were so confident the governors and Stephen Grover Cleveland, the President of the United States at the time, were invited to ride behind John Bull for its first 50-mile leg of the journey- I’m not sure they actually took up the invitation.

At any rate, with an average speed of 25 miles per hour, John Bull set off on the 17th of April and pulled in Chicago on the 22nd of April. Pretty impressive if you ask me. John Bull then ran rides for those attending before setting off back on the 6th of December and arriving back home on the 13th of December.

It was 1927 when John Bull ran again at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad centenary celebrations called the “Fair of the Iron Horse” which honestly sounds more like a love story.

For John Bull’s centenary in 1931, there wasn’t the funds to get it fully operational again so the Smithsonian lifted the locomotive off the track with jacks and ran it stationary with compressed air.

It went to the Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago from 1933-1934 as a static display and at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. By this point, John Bull was becoming too fragile to move around and to be outside. For this reason, it was kept on static display for another 15 years in the Smithsonian.

In 1964 John Bull was moved to its now permanent home- the National Museum of American History, which is still in the Smithsonian Institution.

As its 150th anniversary approached plans came in for the locomotive to run again. And it did. Running under its own steam for the last time in 1981. John Bull is still amongst the oldest locomotives to have moved under its own power- yet everyone always harps on about Flying Scotsman still moving- it’s “only” 100! Come talk to me in 50 years’ time.

But perhaps the most interesting of John Bull’s records is that it is the oldest locomotive to be transported by air which it did in 1985.

The not-So-Romantic Railways: Railroads of America

I dropped a not-so-subtle hint earlier in the blog but I’m delighted to announce the fourth main series addition to the Not-So-Romantic Railways will be The Not-So-Romantic Railways: Railroads of America!

The book will be released on the 2nd of February 2024 and you can pre-order yourself an e-book version right now!

This has actually just been a copy-and-paste job of a blog from the early workings of the book itself!

I’m beyond excited to bring the next main line (railway pun?) to you!

What to read next

If you’ve enjoyed this Not-So-Romantic Blog then here are some more I think you’ll like as well.